The Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) future continues to be uncertain as Texas v. U.S. (known as California v. Texas in the U.S. Supreme Court), remains unresolved. This ongoing litigation challenges the ACA’s minimum essential coverage provision (known as the individual mandate) and raises questions about the entire law’s survival. The individual mandate provides that most people must maintain a minimum level of health insurance coverage; those who do not do so must pay a financial penalty (known as the shared responsibility payment) to the IRS. The individual mandate was upheld as a constitutional exercise of Congress’ taxing power by a five member majority of the Supreme Court in NFIB v. Sebelius in 2012.

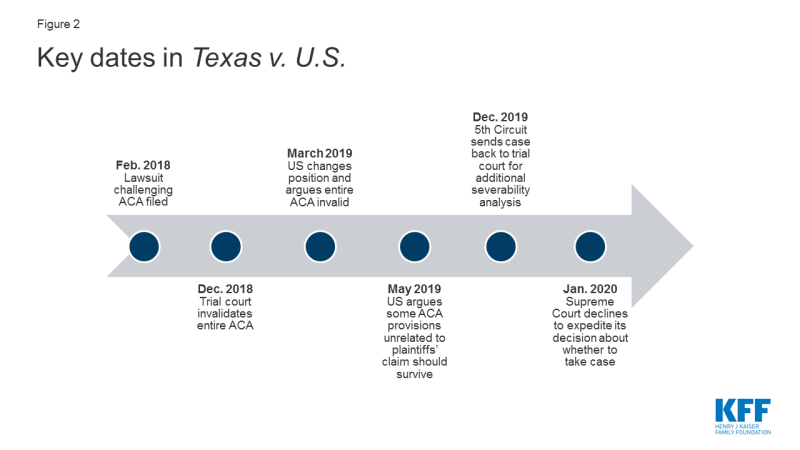

In the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), Congress set the shared responsibility payment at zero dollars as of January 1, 2019, leading to the current litigation. In December 2019, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit affirmed the trial court’s decision that the individual mandate is no longer constitutional because the associated financial penalty no longer “produces at least some revenue” for the federal government. However, instead of deciding whether the rest of the ACA must be struck down, the 5th Circuit sent the case back to the trial court for additional analysis. In the meantime, the parties supporting the ACA have asked the Supreme Court to review the case. The Supreme Court will not expedite this decision, which means that, if the Court does take the case, it likely would be argued and decided in the next term and would not be resolved before the 2020 election.

The ACA remains in effect while the litigation is pending. However, if all or most of the law ultimately is struck down, it will have complex and far-reaching consequences for the nation’s health care system, affecting nearly everyone in some way. A host of ACA provisions could be eliminated, including protections for people with pre-existing conditions, subsidies to make individual health insurance more affordable, expanded eligibility for Medicaid, coverage of young adults up to age 26 under their parents’ insurance policies, coverage of preventive care with no patient cost-sharing, closing of the doughnut hole under Medicare’s drug benefit, and a series of tax increases to fund these initiatives.

This issue brief answers key questions about the litigation as we await a decision from the Supreme Court about whether it will review the case.

1. Who Is Challenging the ACA?

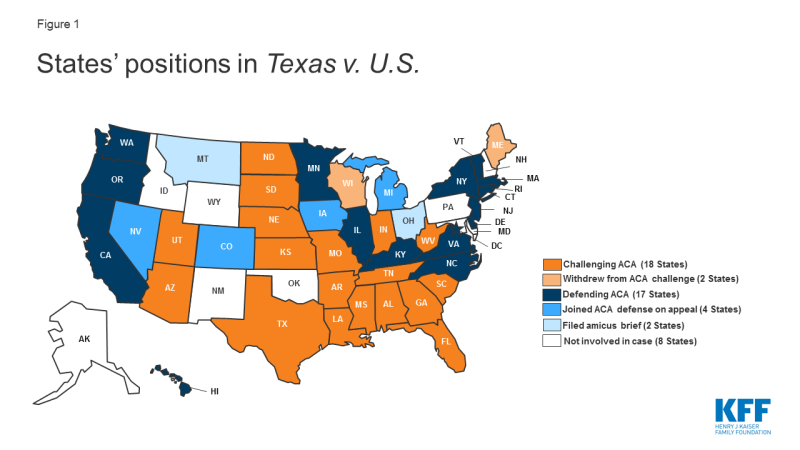

A group of 20 states, led by Texas, sued the federal government in February 2018, seeking to have the entire ACA struck down (the “state plaintiffs”). These states are represented by 18 Republican attorneys general and 2 Republican governors. After Democratic victories in the 2018 mid-term elections, two of these states, Wisconsin and Maine, withdrew from the case in early 2019, leaving 18 states challenging the ACA on appeal (Figure 1).

Two individuals joined the lawsuit in the trial court in April 2018, as plaintiffs challenging the ACA. These plaintiffs are self-employed residents of Texas who claim that the individual mandate requires them to purchase health insurance that they otherwise would not buy, although there is no penalty if they fail to buy coverage.

2. What Is the Federal Government’s Position in the Case, and How Has It Changed Over Time?

When the case was argued in the trial court, the federal government did not defend the constitutionality of the ACA’s individual mandate. Instead, the federal government agreed with the state and individual plaintiffs that the individual mandate is no longer constitutional under Congress’s taxing power as a result of the TCJA provision that set the financial penalty at zero. It is unusual for the federal government to take a position that does not seek to uphold a federal law.

Unlike the plaintiffs, the federal government argued at the trial court that only the ACA’s protections for people with pre-existing conditions, including guaranteed issue and community rating, should be struck down along with the individual mandate. The federal government took the position that these provisions cannot function effectively without the individual mandate but the rest of the ACA should be allowed to survive.

Notably, the federal government changed its position while the case was on appeal at the 5th Circuit (Figure 2). First, the federal government took what the 5th Circuit called a “significant change in litigation position” by deciding to support the trial court’s decision that the individual mandate is inseverable from the entire ACA. This change came after the federal government had appealed, asking the 5th Circuit to review the trial court’s decision. Next, the federal government raised new arguments about the scope of relief that the court should grant, asserting that the federal government should be enjoined from enforcing only the ACA provisions that injure the plaintiffs. For example, the federal government identified “several criminal statutes used to prosecute individuals who defraud our healthcare system” that are part of the ACA that it believes should survive. The federal government also argued for the first time in the 5th Circuit that any injunction prohibiting enforcement of the ACA should apply only in the plaintiff states.

3. Who is Defending the ACA?

Another 17 states, led by California, were permitted by the trial court to intervene in the case and defend the ACA (the “state intervener-defendants”). Subsequently, the 5th Circuit allowed four more states to intervene in the case on appeal, bringing the total number of states defending the ACA in the case to 21 (Figure 1).

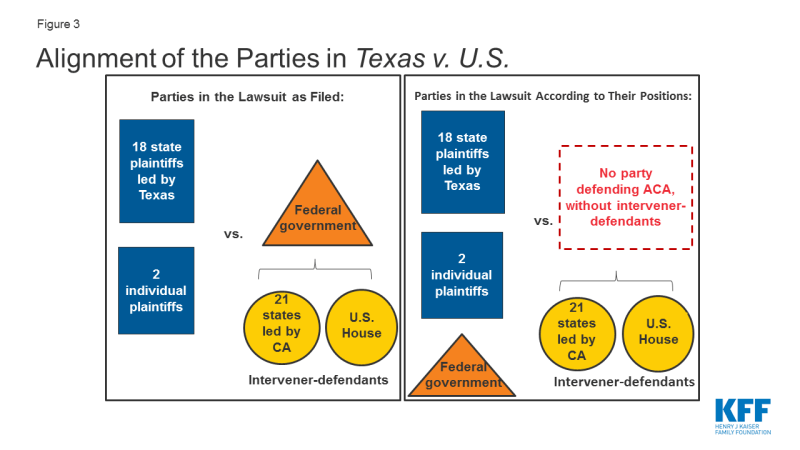

The 5th Circuit also allowed the U.S. House of Representatives to intervene in the case to defend the ACA on appeal. However, the 5th Circuit did not decide whether the House has standing to pursue the appeal. The standing of the state intervener-defendants and/or the House is particularly important in this case, since the federal government is not defending the ACA (Figure 3).

4. What Did the 5th Circuit Decide?

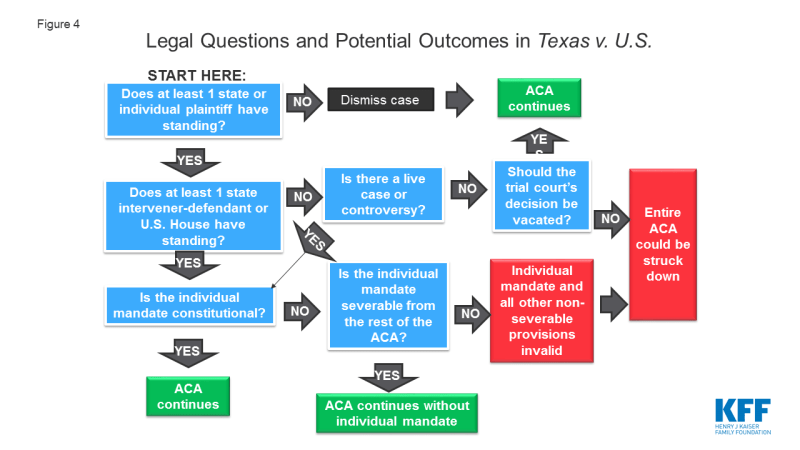

The 5th Circuit issued a 2:1 decision finding the individual mandate unconstitutional and sending the case back to the trial court for additional analysis about whether the rest of the ACA can survive. There are three main issues in the case: (A) whether the parties have standing to invoke the court’s jurisdiction; (B) whether the ACA’s individual mandate, as amended by the TCJA, is constitutional; and (C) if the mandate is unconstitutional, whether it can be severed from the rest of the ACA, or on the other hand, whether other provisions of the ACA also must be invalidated. Figure 4 illustrates the legal questions and potential outcomes in the case.

(A) The parties have standing to litigate the case.

The 5th Circuit decided that the case presented a live controversy for it to resolve, despite the unusual alignment of the parties’ positions. First, the federal government has standing to pursue an appeal. Although the federal government is “in almost complete agreement on the merits of the case” with the plaintiffs, it also has indicated that it will continue to enforce the ACA unless or until a court issues a final order striking the law down. Separately, the state intervener-defendants have standing to pursue an appeal because they would be injured by the loss of federal ACA funding, such as funding for the Medicaid expansion and the Medicaid Community First Choice attendant care program, if the trial court’s decision is upheld.

The 5th Circuit decided that the both the individual and state plaintiffs have standing to challenge the ACA in court. Standing ensures that federal courts are deciding actual cases or controversies as required by the U.S. Constitution. Standing is essential for the court to have jurisdiction to decide a case and therefore cannot be waived. To establish standing, a party must suffer an injury that is concrete and actual or imminent; fairly traceable to the challenged conduct; and likely to be redressed by a favorable court ruling. The 5th Circuit agreed with the trial court that the individual plaintiffs have standing because they have spent money that they otherwise would not have spent, absent the individual mandate, to purchase health insurance. The 5th Circuit also decided that the state plaintiffs have standing because they are incurring costs from the individual mandate from having to verify which state employees have minimum essential coverage.

The dissent reached the opposite conclusion, finding that neither the individual nor the state plaintiffs has standing to bring the case. According to the dissent, any injury experienced by the individual plaintiffs “is entirely self-inflicted” because “absolutely nothing” will happen to them if they do not purchase insurance to meet the individual mandate now that the penalty is set at zero. The dissent also concluded that the state plaintiffs lack standing because they failed to provide evidence showing that “at least some state employees have enrolled in employer-sponsored health insurance” or that “anyone has enrolled in their Medicaid programs solely because of the unenforceable coverage requirement.”

(B) The individual mandate is unconstitutional after the TCJA set the financial penalty at zero.

The 5th Circuit decided that the individual mandate as amended by the TCJA is unconstitutional. The court agreed with the state and individual plaintiffs and the federal government’s assertion that the requirement to produce some revenue is “essential” to the Supreme Court’s earlier finding in NFIB that the individual mandate could be saved as a valid exercise of Congress’s power to tax. Without that feature, the mandate is a command to purchase health insurance, which as the Supreme Court held in in NFIB, is an unconstitutional exercise of Congress’ power to regulate interstate commerce.

The dissent concluded that the individual mandate remains constitutional because the TCJA amendment is “a law that does nothing.” The dissent reasoned that the TCJA did not change the text of the coverage requirement and therefore did not change the individual mandate into a mandatory command to purchase insurance. Rather, Congress “changed the parameters” of the choice about whether to purchase insurance from paying a tax penalty to “no consequences at all.”

(C) The trial court’s analysis about whether the individual mandate is severable from the rest of the ACA was incomplete.

The 5th Circuit sent the case back to the trial court for additional analysis about which ACA provisions should survive without the individual mandate. The trial court incorrectly focused on the intent of Congress in 2010 when passing the ACA and instead should have considered Congress’ intent when enacting the TCJA and setting the shared responsibility payment at zero in 2017. In so doing, the trial court should “employ a finer-toothed comb. . . and conduct a more searching inquiry into which provisions of the ACA Congress intended to be inseverable from the individual mandate. . . us[ing] its best judgment to determine how best to break the ACA down into constituent groups, segments, or provisions to be analyzed.”

The 5th Circuit also directed the trial court to consider the federal government’s new argument that any order prohibiting enforcement of the ACA should extend only to provisions that injure the plaintiffs and apply only in the plaintiff states. The trial court may consider whether the federal government timely raised this argument and whether Supreme Court precedent supports limiting the remedy in this way.

The dissent criticized the majority’s failure to send the case back to the trial court instead of resolving the severability issue. Severability is a question of law, which the 5th Circuit could have resolved without sending the case back to the trial court. The dissent agreed with the majority that the severability analysis should look to the intent of Congress when passing the TCJA in 2017. However, the dissent concluded that the fact that Congress changed the tax penalty amount to zero while leaving the rest of the ACA in place indicates that Congress intended for all of the other provisions to remain in effect.

5. What is Happening at the Supreme Court?

The Supreme Court will decide whether to review the 5th Circuit’s decision according to its regular timeframe; if the Court does take the case, it may not be argued and decided until next year. On January 3, 2020, California and the House filed cert petitions, asking the Court to review three issues decided by the 5th Circuit: whether Texas and the individual plaintiffs have standing to bring the lawsuit challenging the individual mandate; whether the TCJA rendered the individual mandate unconstitutional; and if so, whether the mandate is severable from the rest of the ACA.

The Supreme Court denied the request to expedite its decision about whether to take the case, which could foreclose the possibility of resolving the case during the current term. California and the House asked the Court to proceed on an expedited basis so that the case could be argued and decided by June 2020. After the Court denied the request to expedite, Texas and the individual plaintiffs asked the Court to extend their deadline to respond to the cert petitions. The Supreme Court denied the request to extend the deadline. California and the House pointed out that adhering to the original deadline still could allow the case to be argued and decided during the current term.

California and the House are asking the Supreme Court to review the case without waiting for additional severability analysis from the lower courts. Instead, they argue that the Supreme Court usually agrees to review cases when a lower court finds a federal law unconstitutional, and the Supreme Court should do so now in this case to minimize the amount of time that the ACA’s future remains uncertain. If the Supreme Court does not agree to review the case now, the litigation likely will continue for several more years, while the trial court issues a new decision on severability and that decision is then reviewed by the 5th Circuit, before returning to the Supreme Court. California and the House also argue that the additional severability analysis requested by the 5th Circuit will be unnecessary if the Supreme Court finds the individual mandate constitutional. In opposing the motion to expedite, the federal government acknowledged that lower court decisions invalidating federal laws often warrant Supreme Court review; however, the federal government, along with Texas and the individual plaintiffs, argued that the Supreme Court should let the lower courts come to a final decision on severability before doing so.

Looking Ahead

If the Supreme Court decides to review the case, finds that the individual mandate is unconstitutional, and invalidates only that provision, the practical result will be essentially the same as the ACA exists today, without an enforceable mandate. If the Supreme Court adopts the position that the federal government took during the trial court proceedings and invalidates the individual mandate as well as the protections for people with pre-existing conditions, then federal funding for premium subsidies and the Medicaid expansion would stand, and it would be up to states whether to reinstate the insurance protections. The Supreme Court also could decide that Texas and the individual plaintiffs do not have standing to bring the lawsuit, which would allow the ACA as it exists today to remain in effect.

The most far-reaching consequences, affecting nearly every American in some way, will occur if the Supreme Court ultimately decides that all or most of the ACA must be overturned, as the federal government now argues. The number of non-elderly individuals who are uninsured decreased by 18.6 million from 2010 to 2018, as the ACA went into effect. The ACA made significant changes to the individual insurance market, including requiring protections for people with pre-existing conditions, creating insurance marketplaces, and authorizing premium subsidies for people with low and modest incomes. The ACA also made other sweeping changes throughout the health care system including expanding Medicaid eligibility for low-income adults; requiring private insurance, Medicare, and Medicaid expansion coverage of preventive services with no patient cost sharing; phasing out the Medicare prescription drug doughnut hole coverage gap; reducing the growth of Medicare payments to health care providers and insurers; establishing new national initiatives to promote public health, care quality, and delivery system reforms; and authorizing a variety of tax increases to finance these changes. All of these provisions could be overturned if all or most of the ACA is struck down by the courts, and it would be enormously complex to disentangle these provisions from the overall health care system.

For now, the ACA remains in effect. The trial court’s original decision that the entire ACA should be invalidated was never implemented and now has been set aside by the 5th Circuit. Additionally, the Trump Administration has indicated that it intends to continue enforcing the ACA while the appeal is pending. If the Supreme Court decides to review the case, it likely would not issue a decision until next year. Otherwise, the case will return to the lower courts and likely not reach the Supreme Court again for one or more years. As a result, nearly 10 years after its enactment, the only certainty for the ACA in the foreseeable future is that there is continuing uncertainty about its ultimate survival.