Gov. Matt Bevin (R-KY) wants to end dental and vision coverage, set up “MyRewards” coupon program tied to behavior.

Have you ever thought that health insurance paperwork was too straightforward? Do you really love keeping track of your credit card points and customer loyalty card accounts at retailers? Would you prefer that the government do more to tell you how to live a good life?

Then you’ll love Kentucky Gov. Matt Bevin’s (R) plan to overhaul Medicaid by cutting benefits, charging low-income recipients for services, and making them jump through hoops to earn health coverage points in new “MyRewards Accounts.”

From a glance at Bevin’s proposal, it’s easy to mistake the “MyRewards” idea for an expansion of coverage. The changes are described as “benefit enhancements” in a new, detailed implementation proposal from the consulting firm Deloitte.

Bevin’s plan is in fact a benefit cut. Kentucky’s Medicaid program currently includes vision and dental. If you’re eligible for Medicaid in Kentucky, then you’re eligible for coverage of regular tooth checkups and eye exams under state law.

Bevincare would “enhance” Medicaid benefits by taking several of them away. You will lose the security of knowing your eye doctor and dentist will see you when you need them, and gain the exciting new opportunity to earn chits toward the cost of those same services.

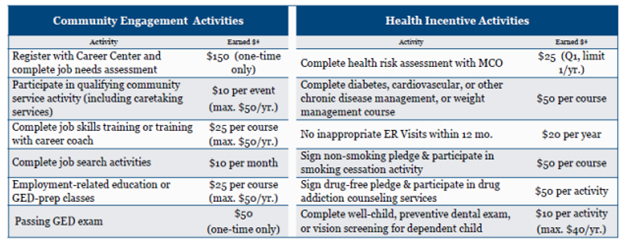

But to accrue those chits, you must live by Bevin’s rules. MyRewards points accumulate based on the enrollee’s participation in job training, health screening, smoking cessation, volunteer, and educational programs, at the rates listed below:

Bevin’s behavioral incentives effectively convert his definition of good character into a state-enforced moral code which everyone who can’t afford health insurance must follow — and whose compliance the state must monitor.

“This requires building a massive database about people’s individual behaviors, and then keeping it up. Never mind that it’s massively expensive, it also feels very invasive,” former Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) administrator Andy Slavitt said in an interview. “I’m not sure the government should be tracking if I put on five pounds, or if I’m advancing in my job, or what grade I got on my GED exam.”

Bevin first shopped the MyRewards idea last summer while drafting up a waiver request to the federal government, after realizing that his campaign promise to end the state’s Medicaid expansion under Obamacare would strip roughly one in six state residents of their health care. Given the political risks of taking health insurance away from hundreds of thousands of people, Bevin opted instead to ask Washington for permission to radically reshape the state’s Medicaid offerings — effectively a smaller stealth cut to insurance access for low-income families.

The biggest change is Bevin’s proposal to charge premiums for Medicaid and impose an annual $1,000 deductible before the program covers beneficiaries’ health care costs. Those are big price hikes for people who can’t afford them. Similar policies have driven down insurance rates and harmed public health outcomes in other states already.

But the MyRewards proposal is more novel, setting the Kentucky governor’s plan apart from other conservatives’ Medicaid sabotage efforts.

The accounts would also be linked to work — or, for the jobless, to participation in state-run job training or volunteer work programs. That structure belies a common conservative misconception about the Medicaid population. Most Medicaid recipients are in fact already working, and three-quarters of all able-bodied working-age recipients who aren’t working, looking for work, or in school are caretakers for a family member.

Bevin’s plan doesn’t account for the realities of Medicaid recipients’ lives, creating the grim specter of “people picking up garbage by the highway in order to get a dental exam,” Slavitt said.

The state can even give you negative “MyRewards” chits — fines, in essence — for going to the emergency room too much. The first ER trip deemed non-emergency in nature costs you $20; the second, $50; and all subsequent episodes, $75 a pop, unless the fines would take your MyRewards balance below a negative-$150 minimum balance.

Bevin’s plan therefore makes it harder for low-income working people to afford primary care attention and then punishes them for showing up to the ER for something a primary care doctor should be able to treat. It’s a self-defeating cycle, quietly incentivizing people to let illnesses linger until they reach a critical point where an ER will admit them — at far higher cost to society — in order to avoid being punished for their inability to afford better care.

The weird feedback loop between imposing premiums and penalizing ER visits also runs directly counter to Bevin’s purported interest in work incentives. Less-covered people are sicker; sicker people are less able to work.

“If the governor wants to promote work, he ought to promote health and simplify things rather than complicate them,” Slavitt said. “If you just cover people for preventive and basic services, then you prevent health needs from exploding and guess what: Then people are able to get jobs.”

Bevin’s planned ER penalties, like most of his waiver proposal, are borrowed from Vice President Mike Pence’s version of Medicaid restrictions in Indiana. As governor, Pence got his Medicaid ideas from the same consultant who Bevin hired: Seema Verma, the current CMS administrator for President Donald Trump’s administration.

(Verma recently recused herself from CMS’ decision about whether to grant Bevin’s waiver; CMS staff under the previous administration rejected pieces of the Pence waiver which was the jumping-off point for Verma’s work in Kentucky.)

The behavioral incentives Verma and Bevin push for Medicaid are not a new idea in health care policy writ large. Employee wellness programs, where the company that’s paying most of your health insurance premiums gives you positive incentives to work out or quit smoking, have been around for decades.

But those voluntary programs are not punitive, and the workers subject to their incentives are not denied care for failing to meet performance goals. Bevin’s MyRewards concept turns the incentives notion on its head, establishing behavioral goals as a floor threshold for determining who deserves eye and tooth care at all.

“It creates a different standard [of behavior] for people who can’t afford health care,” Slavitt said. “If they said, ‘hey we’re going to do this for everybody because we think it’s important,’ that would be different. This just feels punitive.”