Executive Summary

Extensive research and the pandemic have elevated the importance of addressing social determinants of health (SDOH) to improve health and reduce longstanding disparities in health and health care. Social determinants of health include factors like socioeconomic status, education, neighborhood and physical environment, employment, and social support networks, as well as access to health care. Prior to the pandemic, both health and non-health sectors have been engaged in initiatives to address social determinants of health. In addition, in response to the pandemic, legislation has been enacted to provide significant new funding to address the health and economic effects of the pandemic including direct support to address food and housing insecurity as well as stimulus payments to individuals, federal unemployment insurance payments, and expanded child tax credit payments. While measures like these have a direct impact in helping to address SDOH, health programs like Medicaid can also play a supporting role. Although federal Medicaid rules prohibit expenditures for most non-medical services, state Medicaid programs have been developing strategies to identify and address enrollee social needs both within and outside of managed care. CMS released guidance for states about opportunities to use Medicaid and CHIP to address SDOH in January 2021.

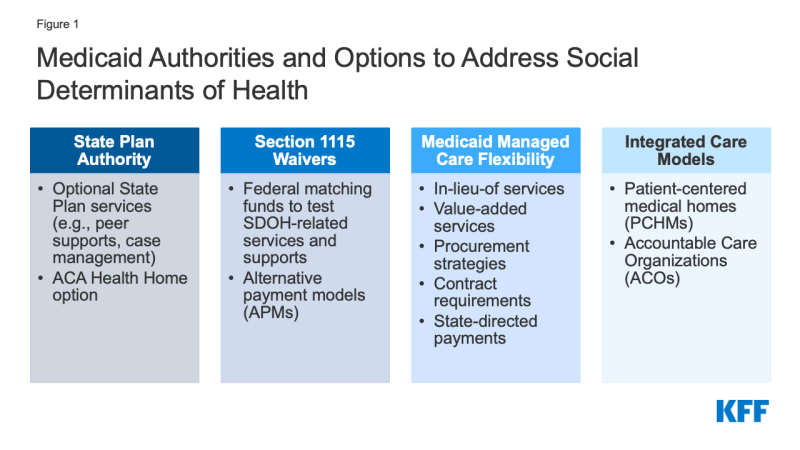

This brief describes options and federal Medicaid authorities states may use to address enrollees’ social determinants of health (Figure 1) and provides state examples, including initiatives launched in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The focus of this brief is on state-driven Medicaid efforts to address social determinants for nonelderly enrollees who do not meet functional status or health need criteria for home and community-based services (HCBS) programs.

Introduction

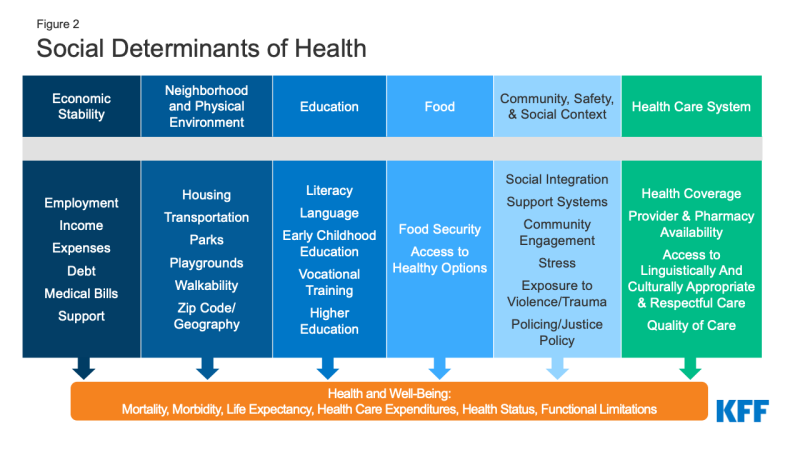

Social determinants of health are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age. They include factors like socioeconomic status, education, neighborhood and physical environment, employment, and social support networks, as well as access to health care (Figure 2).

Though health care is essential to health, research shows that health outcomes are driven by an array of factors, including underlying genetics, health behaviors, social, economic, and environmental factors. While there is currently no consensus in the research on the magnitude of the relative contributions of each of these factors to health, studies suggest that health behaviors and social and economic factors are primary drivers of health outcomes, and social and economic factors can shape individuals’ health behaviors. There is extensive research that concludes that addressing social determinants of health is important for improving health outcomes and reducing health disparities.

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated already existing health disparities for a broad range of populations, but specifically for people of color. Data from the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey show that over the past year, Black and Hispanic adults have fared worse than White adults across nearly all measures of economic and food security. For example, in April 2021, nearly two-thirds of Black adults and seven in ten Hispanic adults (64% and 70%, respectively) reported difficulty paying household expenditures compared to 42% of White adults; 7% of Black adults and 12% of Hispanic adults reported no confidence in their ability to make next month’s housing payment compared to 4% of White adults, and 14% of Black adults and 16% of Hispanic adults reported food insufficiency in the household compared to 5% of White adults. While these disparities in social determinants of health existed prior to the pandemic, the high current levels among certain groups highlights the disproportionate burden of the pandemic on people of color.

Prior to the pandemic there were a variety of initiatives to address social determinants of health both in health and non-health sectors. Outside of the health care system, non-health sector initiatives seek to shape policies and practices in ways that promote health and health equity. Within the health care sector, a broad range of initiatives have been launched at the federal, state, and local levels and by plans and providers to address social determinants of health, including efforts within Medicaid. These efforts stem from increasing rates of coverage under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), new funding and demonstration authorities provided through the ACA, and an increasing shift across the health system toward value- or outcome-based payments and “whole person” care. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Innovation Center (“CMMI”) was authorized under the ACA and is tasked with designing, implementing, and testing new health care payment and service delivery models that aim to improve patient care, lower costs, and better align payment systems to promote patient-centered practices. In April 2017, CMMI launched the “Accountable Health Communities” (AHC) Model to test different approaches to support local communities in addressing the health-related social needs of Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries. The model aims to bridge the gap between clinical and community service providers and was the first CMS innovation model with a primary focus on social determinants of health.

How Medicaid Can Address the Social Determinants of Health?

State Medicaid programs can add certain non-clinical services to home and community-based services (HCBS) programs to support seniors and people with disabilities. Generally, states have not been able to use federal Medicaid funds to pay the direct costs of non-medical services like housing and food. However, within Medicaid, states can use a range of state plan and waiver authorities (e.g., 1905(a), 1915(i), 1915(c), or Section 1115) to add certain non-clinical services to the Medicaid benefit package including case management, housing supports, employment supports, and peer support services. Historically, non-medical services have been included as part of Medicaid home and community-based services (HCBS) programs for people who need help with self-care or household activities as a result of disability or chronic illness.

Outside of Medicaid HCBS authorities, state Medicaid programs have more limited flexibility to address social determinants of health. Certain options exist under Medicaid state plan authority as well as Section 1115 authority to add non-clinical benefits. Additionally, under federal Medicaid managed care rules, managed care plans have some limited flexibility to pay for non-medical services. Other Medicaid payment and delivery system reforms, like the formation of Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), may provide flexibility or opportunities to cover non-medical services that support health as well.

To encourage the adoption of strategies that address the social determinants of health in Medicaid and CHIP, CMS released guidance for states in January 2021. The remaining sections outline the primary Medicaid authorities and flexibilities that can be used to add benefits and design programs to address the social determinants of health for nonelderly enrollees who do not meet functional status or health need criteria for Medicaid home and community-based services (HCBS) programs. Some efforts may address a single issue (e.g., housing, or food security) while other efforts and initiatives are designed to address a range of social determinants of health.

What State Plan Authority Exists to Address SDOH in Medicaid?

States may elect to include optional benefits that address social determinants under Section 1905(a) State Plan authority. For example, states may include rehabilitative services, including peer supports and/or case management (or “targeted” case management) services, under their Medicaid state plan. States that choose to offer these services frequently target services based on health or functional need criteria. Peer supports can help individuals coordinate care and social supports and services, facilitating linkages to housing, transportation, employment, nutrition services, and other community-based supports. Case management services can also assist individuals in gaining access to medical, social, educational, and other services. Case management services are frequently an important component of HCBS programs but can also be used to address a broader range of enrollee needs.

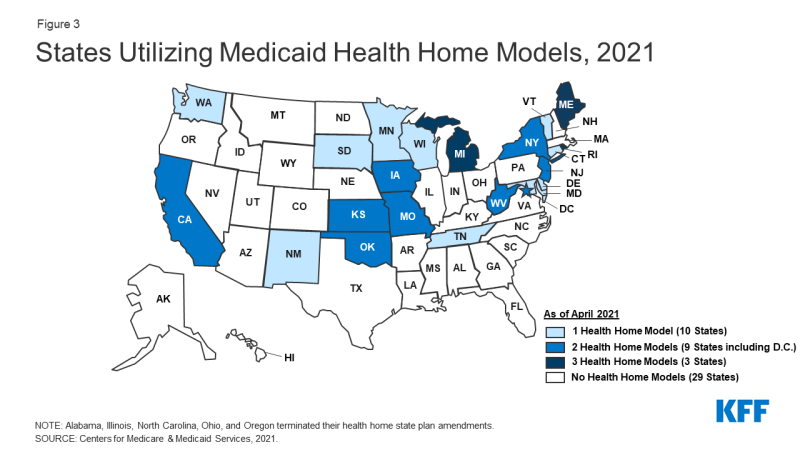

States can provide broader services to support health through the optional health home state plan benefit option established by the ACA (Figure 3). Under this option (Section 1945), states can establish health homes to coordinate care for people who have chronic conditions. Health home services include comprehensive care management, care coordination, health promotion, comprehensive transitional care, patient and family support, as well as referrals to community and social support services (such as housing, transportation, employment, or nutritional services). States receive a 90% federal match rate for qualified health home service expenditures for the first eight quarters under each health home SPA., A federally funded evaluation of the health homes model found that most providers reported significant growth in their ability to connect patients to nonclinical social services and supports under the model, but that lack of stable housing and transportation were common problems for many enrollees that were difficult for providers to address with insufficient affordable housing and rent support resources.

How Can States Use Section 1115 Waivers to Address SDOH?

Through Section 1115 authority, states can test approaches for addressing SDOH including requesting federal matching funds to test SDOH related services and supports in ways that promote Medicaid program objectives. States can obtain approval for Section 1115 demonstration waivers that test broad changes in Medicaid eligibility, benefits and cost-sharing, and payment and delivery systems as long as the Secretary determines that the demonstration is furthering the objectives of the Medicaid program. While not required by statute, longstanding policy requires that Section 1115 waivers be budget neutral for the federal government. States must conduct independent evaluations of Section 1115 demonstrations to determine their impact and effectiveness. States can request federal matching funds through Section 1115 to test the effectiveness of providing services like one-time community transition services (to supportive housing) for individuals experiencing or at-risk of homelessness or chore or cleaning services for individuals with poor asthma control. States can pilot services for a specific population (e.g., by age or defined risk factors) or a limited geographic area. States can also test alternative payment methodologies (APMs) under Section 1115 authority.

The Obama and Trump administrations used major initiatives under Section 1115 Waivers in very different ways to address SDOH. Section 1115 waivers generally reflect priorities identified by states and CMS, as well as changing priorities from one presidential administration to another. Under Section 1115, the Obama administration approved a number of Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) waivers which have provided states with significant federal funding to support hospitals and other providers, changed how care was delivered to Medicaid beneficiaries, and also aimed to address social determinants of health. For example, in New York, provider systems had the option to implement DSRIP projects aimed at ensuring that people had supportive housing. The state has also invested significant state dollars outside of its DSRIP waiver in housing stock to ensure that a better supply of appropriate housing is available. In Texas, some providers used DSRIP funds to install refrigerators in homeless shelters to improve individuals’ access to insulin. California’s original DSRIP waiver increased the extent to which the public hospital systems focused on coordination with social services agencies and county-level welfare offices. Although DSRIP funding was never intended to be permanent, the Trump administration reduced funding for DSRIP renewals and did not approved new DSRIP demonstrations.

The Trump administration issued guidance in January 2018 inviting states to request Section 1115 waivers to impose work requirements in Medicaid as a condition of eligibility with the stated goals of addressing social determinants of health and improving health outcomes. The Arkansas and New Hampshire work requirement cases are still pending at the Supreme Court; however, the Biden administration has rescinded this guidance and has begun the process of withdrawing state work requirement waivers, indicating work requirements do not further Medicaid program objectives. These efforts stood in contrast to other social determinants of health initiatives that used expanded coverage or services to support health-related needs.

| In October 2018, CMS approved North Carolina’s Section 1115 waiver which provides financing for a new pilot program, called “Healthy Opportunities Pilots,” to cover non-medical services that address specific social needs linked to health/health outcomes. The pilots will address housing instability, transportation insecurity, food insecurity, interpersonal violence, and toxic stress for a limited number of high-need enrollees. CMS authorized $650 million in Medicaid funding for the pilot over five years, $100 million of which will be available for capacity building. Eligible beneficiaries must be enrolled in a managed care plan and must have at least one physical or behavioral health risk factor (i.e., adults with two or more chronic conditions or repeated ER or hospital admissions, high-risk pregnant women, or high-risk infants and children) and at least one social risk factor (e.g., homelessness or housing insecurity, food insecurity, transportation insecurity, or interpersonal violence risk). Pilot services will include evidence-based enhanced case management and other services designed to address enrollee needs related to housing, food, transportation, and interpersonal safety. For example, pilot services may include housing modifications (e.g., carpet replacement, air conditioner repair) to improve a child’s uncontrolled asthma control, travel vouchers to a community-based food pantry or a medically-targeted healthy food box for an adult with diabetes living in a rural food desert, or assistance securing safe housing for a pregnant woman experiencing interpersonal violence. Healthy Opportunities “Network Leads” (formerly referred to as “Lead Pilot Entities”) will develop, contract with, and manage the network of human service organizations that will deliver pilot services. In May 2021, the NC Department of Health and Human Services announced the selection of three organizations that will serve as Network Leads. Pilot services are expected to begin in the Spring of 2022.

Washington’s Section 1115 Medicaid Transformation Project leverages “Accountable Communities of Health” (ACHs) as lead entities to align priorities, partners from the traditional and non-traditional sectors, resources, and actions to transform the Medicaid delivery system. CMS authorized up to $994 million in federal financial participation over five years (January 2017 – December 2021) for ACH-related performance-based incentive payments to ACH partnering providers or managed care organizations (MCOs) that support delivery system transformation efforts. ACHs coordinate and oversee regional projects designed to improve care for Medicaid enrollees with an emphasis on building health system capacity, care delivery redesign, prevention, health promotion, and preparing providers for value-based payments. ACH decision-making bodies must include health care partners (e.g., providers, health plans, hospitals/health systems, etc.) as well as multiple community partners and community-based organizations that provide social support services that address the social determinants of health (e.g., transportation, housing, employment services, education, criminal justice, child care etc.). While ACH performance measures/outcomes were designed to be largely clinical in nature, the initiative is based on the premise that social health, public health, and community-based organizations must play a role with the clinical delivery system in order to achieve these outcomes. The state is currently seeking approval from CMS to extend its Section 1115 Medicaid Transformation demonstration for one additional year. California’s “Whole Person Care” (WPC) pilot program aims to coordinate care (physical, behavioral health, and social services) for high-risk, high-utilizing Medi-Cal enrollees and increase integration and data sharing among county agencies, health plans, and other community-based organizations. In 2016, California began its Whole Person Care pilot program, authorized under Section 1115. The waiver authorized up to $1.5 billion in federal funds over five years for the WPC pilot. California’s Department of Health Care Services selected 25 WPC pilots (spanning 26 counties) to participate in the program across the state. Each individual WPC pilot program defines its target population and interventions, within state guidelines. Primary target populations include high utilizers (i.e., those with avoidable use of the emergency room, hospital admission, etc.), individuals experiencing homelessness or are at-risk of homelessness, individuals with multiple chronic conditions, individuals with severe mental illness or substance use disorders (SMI/SUD), and justice-involved individuals. WPC pilot beneficiaries receive care coordination and other services not covered by Medi-Cal to address medical, behavioral health, and social needs. Common services offered by WPC pilots include housing-related services (e.g., housing navigation, tenancy support, landlord incentives), employment assistance, medical respite, and sobering centers. WPC was scheduled to end in December 2020 but has been extended through December 2021 under the state’s current Section 1115 waiver. The state plans to incorporate some of the services offered through its WPC pilots under its “California Advancing and Innovating Medi-Cal” (CalAIM) initiative., |

During the current public health emergency, some states have proposed broader use of Section 1115 demonstration authority to address social determinants of health that were not approved. Under the Trump administration, CMS announced it would not approve Medicaid Section 1115 waivers to provide housing or additional nutrition services despite states seeking to use Section 1115 authority in response to the COVID-19 pandemic for activities including the provision of temporary housing for homeless individuals who test positive for coronavirus, the use of Medicaid funds to cover coronavirus-related testing and treatment for individuals in jails and prisons, and the establishment of a disaster relief fund proposed by one state to cover housing and nutrition supports and non-emergency transportation. Other administrations have used Section 1115 authority more broadly in response to public health emergencies to expand coverage or support providers without regard to budget neutrality rules.

What Medicaid Managed Care Plan Authority Exists to Address SDOH?

With over two-thirds of Medicaid beneficiaries enrolled in comprehensive, risk-based managed care plans nationally, health plans can be an important part of efforts to address enrollee social determinants of health. States pay Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) a set per member per month payment for the Medicaid services specified in their contracts. Capitation rates provide upfront fixed payments to plans for expected utilization of covered services, administration costs, and profit. Plan rates are usually set for a 12-month rating period and must be reviewed and approved by CMS each year. Medicaid managed care plans are required to meet access and quality standards. States develop these standards within federal guidelines and monitor plan performance.

Under federal Medicaid managed care rules, Medicaid MCOs can be given flexibility to pay for non-medical services through “in-lieu-of” authority and/or “value-added” services. “In-lieu-of” services are a substitute for covered services and may qualify as a covered service for the purposes of capitation rate setting, as long as the state determines in-lieu-of services are medically appropriate and cost effective. Enrollees are not required to use the alternative service or setting but may choose to do so. Approved in-lieu-of services are authorized and identified in MCO contracts. For example, a state could authorize in-home prenatal visits for at-risk pregnant beneficiaries as an alternative to traditional office visits. “Value-added” services are extra services outside of covered contract services and do not qualify as a covered service for the purpose of capitation rate setting. Value-added services are provided by MCOs voluntarily. Value-added services examples include safe sleeping spaces for infants, repairs and cleaning services to reduce asthma triggers, installation of a shower grab bar, or health play and exercise programs.

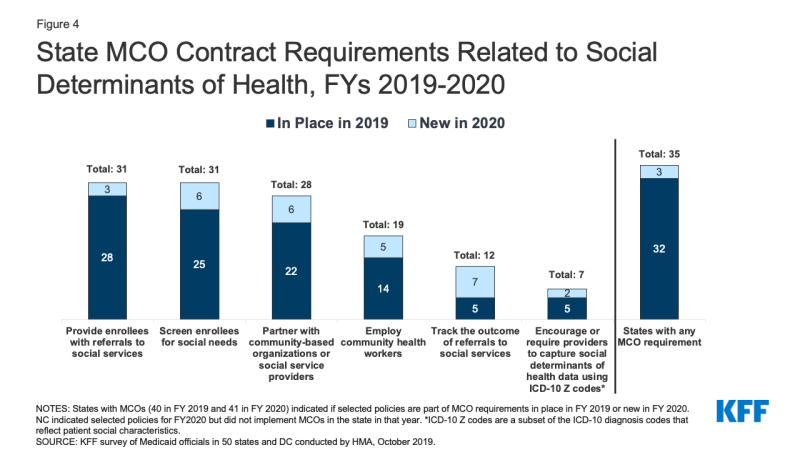

States may implement MCO procurement and contracting strategies, including quality requirements linked to SDOH. In a 2019 KFF survey of Medicaid directors, over three-quarters (35 states) of the 41 MCO states reported leveraging Medicaid MCO contracts to promote at least one strategy to address social determinants of health in FY 2020 (Figure 4). Three-quarters of MCO states reported requiring MCOs to screen enrollees for social needs; provide enrollees with referrals to social services; or partner with community-based organizations. Almost half of states reported requiring MCOs to employ community health workers (CHWs) or other non-traditional health workers. States can also leverage managed care quality requirements to address social determinants of health and may use incentive payments to reward plans for investments and/or improvements in SDOH. For example, states may provide incentive payments to plans that improve health outcomes and lower costs. States can pursue other policies to encourage plan investment in SDOH efforts including requiring plans that exceed a profit margin threshold (established by the state) to reinvest excess profits into SDOH activities. Many plans have developed initiatives and engaged in activities to address enrollees’ social needs beyond state requirements; however, it is difficult to compile national data to reflect this.

States can direct that managed care plans make payments to their network providers using methodologies approved by CMS to further state goals and priorities, including those related to addressing social determinants of health. States can seek CMS approval to require MCOs to implement value-based purchasing models for provider reimbursement (e.g., pay for performance, bundled payments) or participate in multi-payer or Medicaid-specific delivery system reform or performance improvement initiatives. For example, a state may require managed care plans to implement alternative payment models (APMs) or incentive payments to encourage providers to screen for socioeconomic risk factors.

|

A 2020 KFF survey of state Medicaid directors revealed an increasing focus on social determinants, including among Medicaid managed care plans, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. States reported new initiatives and policies implemented during the Public Health Emergency (PHE) to address social determinants (e.g., a food security interagency working group, an eviction diversion program, and shelter options for sick or medically vulnerable individuals who lack stable housing) – noting these initiatives were frequently broader than the Medicaid program but may provide assistance to individuals with Medicaid coverage. In response to an open-ended question, several states that contract with comprehensive Medicaid MCOs reported a variety of initiatives at the MCO-level including food assistance initiatives, expanded pharmacy home deliveries, and MCO-provided gift cards to purchase food and other goods. Some other states also reported MCO policy and contracting changes like Massachusetts, which directed its MCOs to contract with Community Support Program providers working in emergency overnight shelters that were expanded as a result of the pandemic.

What Delivery System Reform Models Can Be Used to Address SDOH?

Integrated care models, including patient-centered medical home (PMCHs) and Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), often emphasize person-centered, comprehensive care and typically involve partnerships with community-based organizations and social services agencies. Integrated care models might address social determinants of health through interdisciplinary care teams or care coordination services. Payment mechanisms tied to these models (e.g., per member per month payments with or without quality or cost incentives) or shared savings/risk models with quality requirements) may provide incentives for providers to address the broad needs of Medicaid beneficiaries.

| Central to Rhode Island’s Medicaid “Accountable Entity” program is accountability for identifying enrollee health-related social needs and supporting the provision of appropriate services. In Rhode Island, Medicaid MCOs sub-contract with integrated provider organizations – called Accountable Entities – responsible for total cost of care and health care quality and outcomes for an attributed population. Accountable Entities must integrate strategies to address social determinants. State certification standards require Accountable Entities to identify three key domains of social need as well as capacity to address those domains. Domains include housing stabilization and support, education, food security, safety and domestic violence, employment, and transportation. The Accountable Entity program requires providers to screen for unmet needs and encourages closer ties between health care providers and community-based organizations (CBOs). In May 2021, the state announced plans to launch the “Community Referral Platform” to support Accountable Entities in systematically screening and referring Medicaid enrollees to social service entities and CBOs to seek services for social need. The platform will allow health care providers to initiate referrals and enable CBOs to inform the provider of the status or outcome of the referral.

Connecticut is a non-MCO state but operates performance-based contracts with its Administrative Services Organizations (ASOs), which are heavily data driven and focused on care integration and delivery system reform, including initiatives to address enrollee social determinants of health. Connecticut operates a managed fee-for-service model and contracts with three Administrative Services Organizations focused respectively on medical, behavioral health, and dental services. The state includes threshold questions concerning food security, housing stability, and physical safety into the medical ASO’s member assessment tool for intensive care management services. Community Health Workers help to deliver intensive case management services overseen by the medical and behavioral health ASOs. Connecticut requires participating practices of its PCMH+ program (an upside-only shared savings initiative) to have formal agreements with community partners (e.g., housing entities, food pantries). The state also encourages providers to capture ICD-10 Z codes on claims to help identify beneficiaries who may need assistance and connect them to community resources and supports. |

LOOKING AHEAD

The pandemic has elevated the importance of addressing social determinants of health to improve health and reduce longstanding disparities in health and health care. While new funding to provide targeted assistance related to food and housing security as well as economic supports to individuals have a direct impact on helping to address SDOH, health programs like Medicaid can also play a supporting role. Although federal Medicaid rules prohibit expenditures for most non-medical services, state Medicaid programs have been developing strategies to identify and address enrollee social needs both within and outside of managed care since long before the COVID-19 pandemic. Although not discussed in this paper, health plan, health system, and other locally driven initiatives have also played a significant role in advancing work in this area. The January 2021 CMS guidance outlines the Medicaid authorities and options states can use to address the social determinants of health.

Although there are opportunities for states within Medicaid to help address SDOH, states also face challenges in designing programs and identifying “best practices” as well as in financing and scaling these efforts. These initiatives require working across siloed sectors with separate funding streams, where investments in one area may accrue savings in another. The capacity of community-based organizations and local programs may not be sufficient to meet identified needs and data infrastructure may need to be improved to allow for data sharing across health care and social services settings. While there is some evidence, more rigorous research is needed to evaluate how addressing social needs impacts health care utilization, spending, and health outcomes.,,, Evaluations of existing programs and waivers, including North Carolina’s Healthy Opportunities pilot program, may yield important evidence about how addressing certain non-medical needs may impact program costs and health outcomes for targeted, at-risk populations.

As Section 1115 waivers reflect changing priorities from one presidential administration to another (from DSRIP to work requirements), it remains to be seen how the Biden administration will use these waivers to further its priorities. The administration may use these waivers as a vehicle to encourage states in their efforts to address SDOH and reduce health disparities. Although the Supreme Court has not yet acted to decide the consolidated Medicaid work requirement cases, the Biden administration is reversing these policies and has withdrawn work requirement waiver authorities in states that gained approval under the Trump administration. Outside of Section 1115, states have other tools to address the social determinants of health including partnering with managed care plans and leveraging managed care contracts, adding optional state plan benefits, and implementing integrated care models with a focus on interdisciplinary teams and “whole person” care.