Under the Trump Administration, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued guidance for state Medicaid waiver proposals that would impose work requirements in Medicaid as a condition of eligibility, and several states have received approval for or are pursuing these waivers. Work requirement waivers generally require beneficiaries to verify their participation in certain activities, such as employment, job search, or job training programs, for a certain number of hours per week or verify an exemption to receive or retain Medicaid coverage. Details about the specific number of hours, approved activities, exemptions, reporting process, and populations included (e.g., expansion adults and/or low-income parents, age) vary across states. As a result of litigation challenging work requirements, three states (Arkansas, Kentucky and New Hampshire) have had such waivers set aside by the courts. As of July 2019, Indiana is the only other state to have implemented a work requirement waiver. Five more states have approved waivers that are not yet implemented, and another seven states have waiver requests pending with CMS. This brief builds on previous analyses to analyze data on Medicaid enrollees and work and examine some of the policy implications of work requirements. Appendix tables provide state-level data. Key findings include the following:

- Most Medicaid adults are already working; among those who are not working, most report barriers to work. Those with better health and more education are more likely to be working.

- Most Medicaid adults who work are working full-time for the full year but are working in low-wage jobs in industries with low employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) offer rates. Industries and occupations with the largest number of workers covered by Medicaid often include jobs that are physically demanding such as food service or construction. Even when working, adults with Medicaid face high rates of financial and food insecurity, as they are still living in or near poverty.

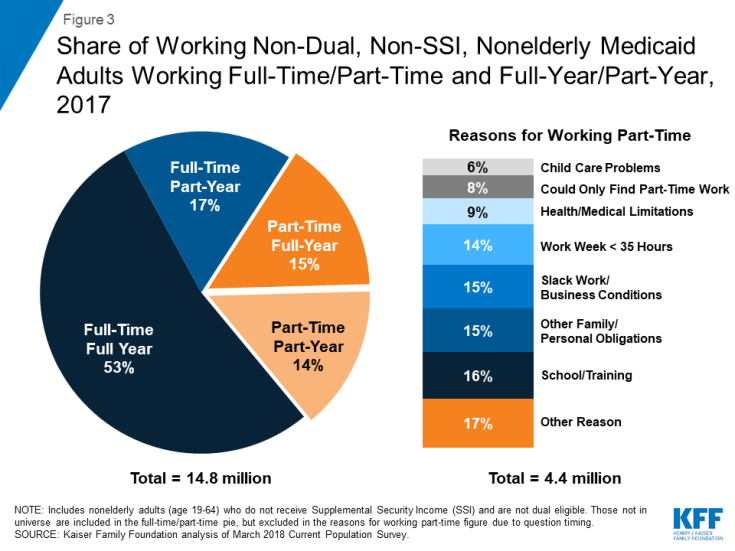

- Many Medicaid enrollees face barriers to work such as functional disabilities, serious medical conditions, school attendance, and care-taking responsibilities. Many Medicaid adults do not use computers, the internet or email, which could be a barrier in finding a job or complying with policies to report work or exemption status.

- People who remain eligible for coverage could lose coverage as a result of reporting requirements, and work requirements may not result in increased employment or employer-based health coverage.

The outcome of the pending litigation, experience of states’ implementation of approved waivers and the outcome of pending waiver requests in non-expansion states will have implications for Medicaid enrollees and for states seeking to adopt similar policies.

What is the work status of Medicaid adults?

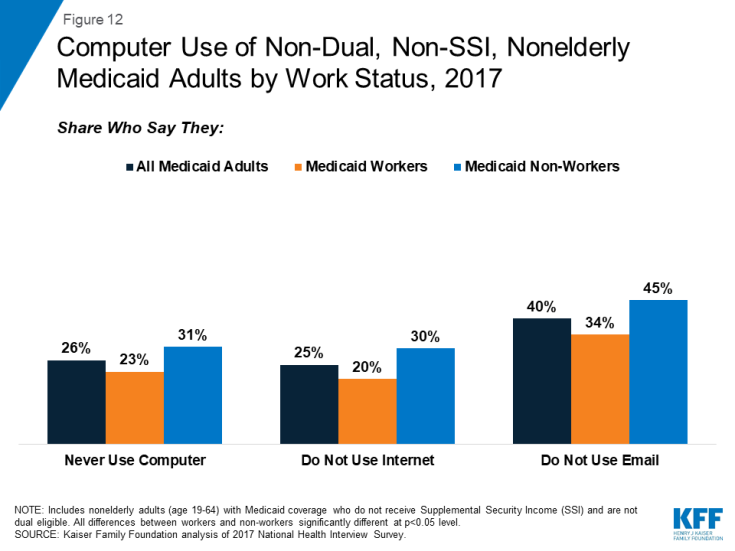

Most Medicaid adults are already working; among those who are not working, most report potential barriers to work (Figure 1). Overall, more than six in ten (63%) non-dual, non-SSI, nonelderly adults with Medicaid (referred to hereafter as Medicaid adults) are working either full or part-time. Even though individuals qualifying for Medicaid on the basis of a disability (e.g., by receiving SSI) and those dually eligible for Medicare are not subject to work requirements under CMS policy and therefore were excluded from this analysis, illness or disability was a primary reason for not working among the remaining Medicaid adults. Caregiving responsibilities or school attendance were other leading reasons reported for not working. The remaining seven percent of Medicaid adults report that they are retired, unable to find work, or not working for another reason. This small group of Medicaid adult enrollees could be the primary group targeted under Medicaid work requirement policies.

Figure 1: The large majority of Medicaid adults are already working or report potential barriers to work.

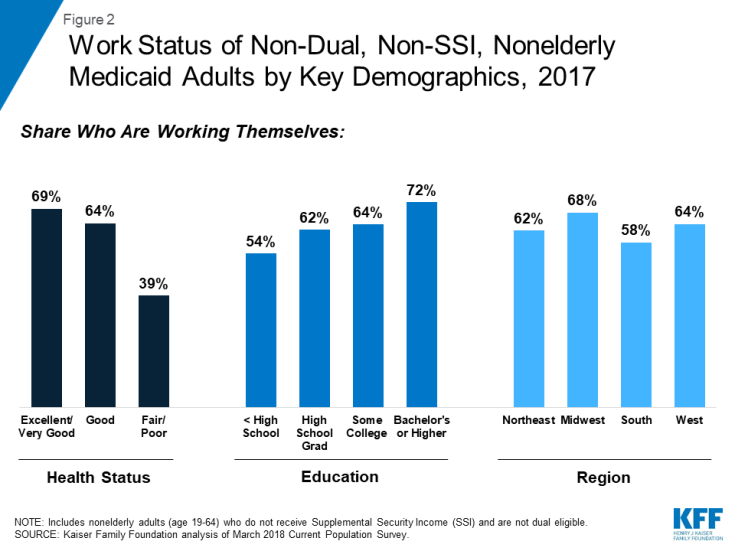

Those in better health and with more education are more likely to be working (Figure 2). Health status is the strongest predictor of work, with people in excellent or very good health thirty percentage points more likely to be working than those in fair or poor health. Education level is also a strong predictor of work. Although “work readiness” encompasses a range of factors, including social/behavioral skills, technical skills, “soft skills,” and others,, having a high school diploma is a basic requirement for many jobs. Rates of work also vary by geographic region, age, and race/ethnicity. Medicaid adults living in the South are less likely to work compared to other regions. Medicaid eligibility levels are lower in the South, so more workers would be less likely to qualify for Medicaid compared to other regions. Those middle aged (26-45) and male are more likely to work than other ages and females (Table 1).

| Total | Share Who Worked | ||

| Total | 23,490,000 | 63% | |

| Age | Under 26 | 5,450,000 | 61%* |

| 26 – 45 | 11,041,000 | 68% | |

| 46 or older | 6,998,000 | 57%* | |

| Sex | Male | 10,377,000 | 69% |

| Female | 13,112,000 | 58%* | |

| Race/Ethnicity | White Non-Hispanic | 10,939,000 | 63% |

| Black Non-Hispanic | 3,947,000 | 59%* | |

| Hispanic | 6,245,000 | 64% | |

| Asian, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander | 1,693,000 | 61% | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 297,000 | 58% | |

| Multiple Races | 369,000 | 71%* | |

| Education | Less than High School | 4,162,000 | 54%* |

| High School Graduate | 8,319,000 | 62%* | |

| Some College | 7,077,000 | 64%* | |

| Bachelor’s Degree or Higher | 3,931,000 | 72% | |

| Geographic Region | Northeast | 5,231,000 | 62% |

| Midwest | 4,762,000 | 68%* | |

| South | 5,906,000 | 58%* | |

| West | 7,591,000 | 64% | |

| Metro Status | Non-Metro^ | 3,347,000 | 64% |

| Metro | 20,143,000 | 63% | |

| Family Type | One Parent with Children | 2,166,000 | 76%* |

| Two Parents with Children | 4,654,000 | 69% | |

| Multi-generational | 1,652,000 | 57%* | |

| Married Adults | 11,598,000 | 58%* | |

| Other | 3,418,000 | 63%* | |

| Family Work Status | Multiple Full-Time Workers in Family | 4,917,000 | 88% |

| One Full-Time Worker in Family | 10,617,000 | 72%* | |

| Only Part-Time Workers in Family | 3,391,000 | 82%* | |

| No Workers in Family | 4,565,000 | 0%* | |

| Self-Reported Health | Excellent/Very Good | 12,037,000 | 69% |

| Good | 7,562,000 | 64%* | |

| Fair/Poor | 3,890,000 | 39%* | |

| NOTE: * indicates statistically significant difference from italicized reference group at p<0.05 level. ^ Non-Metro includes people in not-identified areas. SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of March 2018 Current Population Survey. |

|||

What do we know about Medicaid adults who are working?

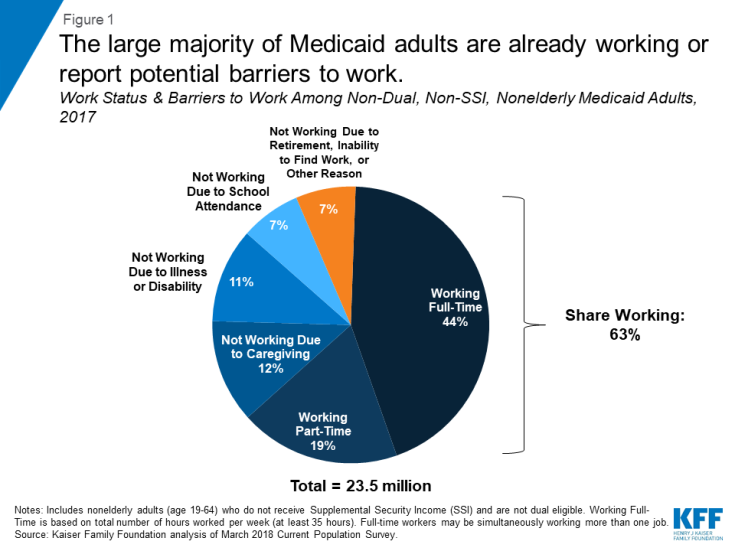

Most Medicaid adults who work are working full-time for the full year. Among Medicaid adults who work, the majority (53%) worked full-time (at least 35 hours per week) for the entire year (at least 50 weeks) (Table 2). Full-time work of 35 hours or more per week may be from more than one job (other data show that nearly one in ten Medicaid workers have more than one job). Among Medicaid adults who work part-time (30% of all workers), many cite reasons such as school or training (16%) or shorter work weeks (less than 35 hours per week) (14%) as the reason they work part-time versus full-time. Other major reasons for part-time work are other family or personal obligations (15%) or slack work/business conditions (15%). Inability to find full-time work, childcare problems, health/medical limitations, and other reasons are the remaining grounds for working part-time, which together account for one-third of part-time Medicaid workers (Figure 3). Medicaid workers have low rates of absenteeism: on average, they report missing five days of work in the previous 12 months due to illness or injury.

Figure 3: Share of Working Non-Dual, Non-SSI, Nonelderly Medicaid Adults Working Full-Time/Part-Time and Full-Year/Part-Year, 2017

| Total | 14,754,000 | |

| Work Status | Full-Time^ | 70% |

| Full-Time, Full-Year | 53% | |

| Full-Time, Part-Year | 17% | |

| Part-Time | 30% | |

| Part-Time, Full-Year | 15% | |

| Part-Time, Part-Year | 14% | |

| Number of Weeks Worked During the Year | 1-12 weeks | 7% |

| 13-25 weeks | 7% | |

| 26-38 weeks | 9% | |

| 39-51 weeks | 12% | |

| 52 weeks | 66% | |

| Firm Size | < 50 employees | 41% |

| 50 – 99 employees | 7% | |

| 100+ employees | 52% | |

| ^ Full-Time is based on total number of hours worked per week (at least 35 hours). Full-time workers may be simultaneously working more than one-job. Numbers may not sum due to rounding. SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of March 2018 Current Population Survey. |

||

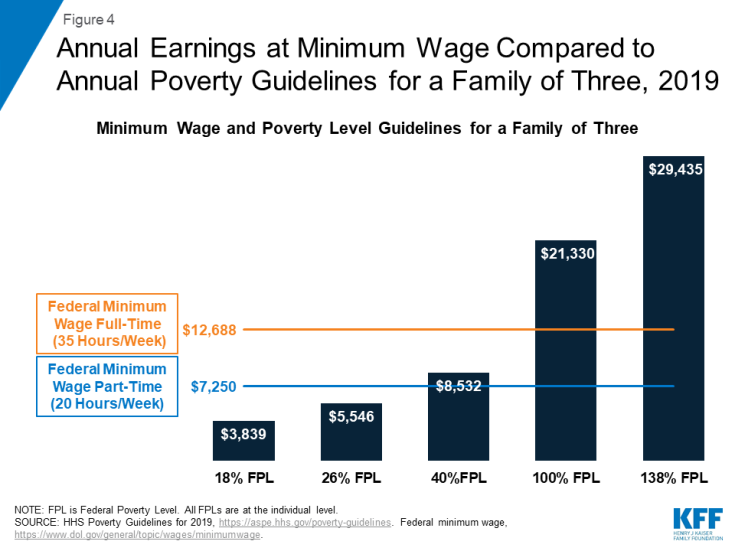

Adults who work full-time for the full year may still be eligible for Medicaid in expansion states because they are working low-wage jobs (Figure 4). An individual working full-time (35 hours/week) for the full year at the federal minimum wage ($7.25 per hour) earns an annual salary of just over $12,688 a year, just below the federal poverty level (FPL) for an individual in 2019. This income is below the Medicaid eligibility limit of 138% FPL for nearly all nonelderly adults in expansion states ($17,236/year for an individual or $29,435 for a family of three in 2019). Medicaid adults who work full-time or part-time in non-expansion states could become ineligible for Medicaid, where median eligibility limit for parents is 40% FPL ($8,532/year for a family of three), and childless adults are not eligible (except in Wisconsin). Eligibility is much lower in many non-expansion states, including Alabama (18% FPL) and Mississippi (26% FPL), two states with pending work requirement waivers. Since individuals with incomes below poverty are not eligible for subsidies for coverage through ACA Marketplaces, working adults in non-expansion states fall into a coverage gap without access to affordable health insurance through their job, Medicaid, or the Marketplace.

Figure 4: Annual Earnings at Minimum Wage Compared to Annual Poverty Guidelines for a Family of Three, 2019

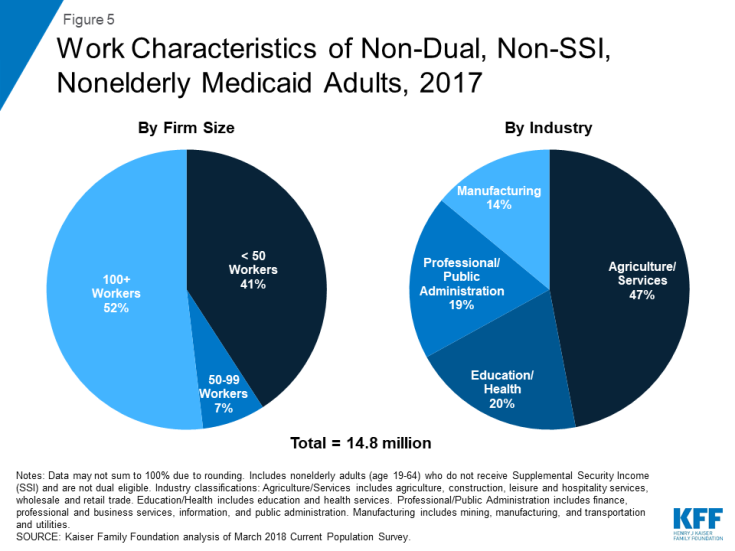

Many Medicaid adults who work are employed by small firms and in industries that have low employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) offer rates. More than four in ten Medicaid workers are employed in firms with fewer than 50 employees, which are not subject to ACA penalties for not offering affordable health coverage (Figure 5). Many Medicaid workers are employed in industries with historically low ESI offer rates, such as the agriculture and service industries. Only about four in ten (38%) Medicaid workers have an offer of ESI, and this coverage may not meet affordability requirements under the ACA. In addition, many Medicaid workers report limited fringe benefits: only 26% of Medicaid workers have paid sick time at their job. Only 8% of Medicaid workers are members of a union, which generally use collective bargaining to negotiate higher wages or benefits for members.

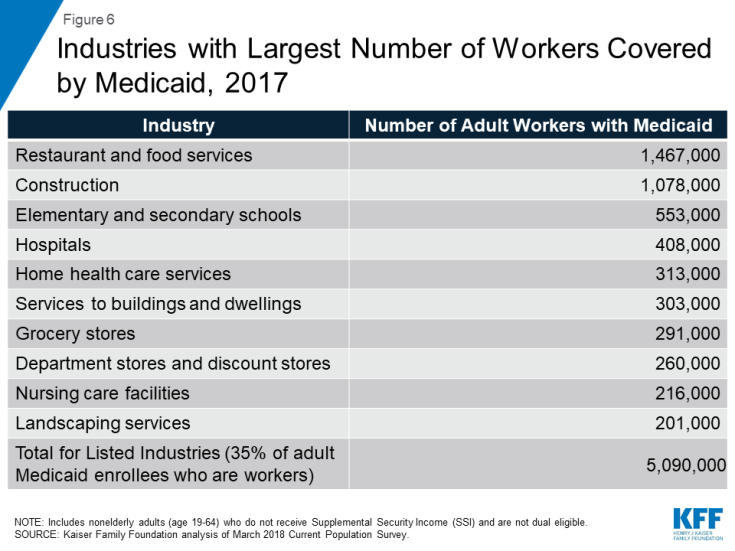

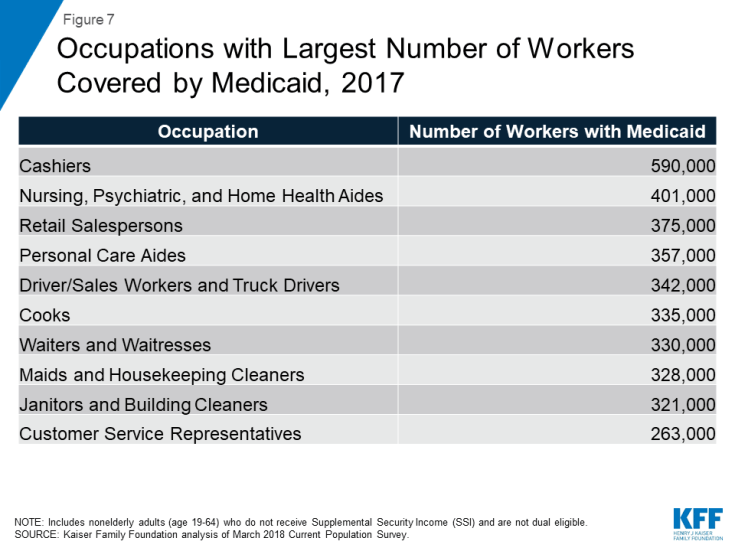

Many Medicaid workers are employed in jobs that are physically demanding. A closer look by specific industry shows that more than a third of working Medicaid adults are employed in ten industries, with one in 10 enrollees working in restaurants or food services (Figure 6). Such jobs typically require physical tasks such as standing, walking, lifting, and carrying. The next largest group of Medicaid workers are employed in the construction industry, which also involves physical labor. When looking at specific occupations, Medicaid workers are largely employed in retail service jobs or jobs that can be physically demanding, such as nursing or personal care aide, cook or waiter/waitress, and janitor or housekeeping. Other top occupations among Medicaid workers include: cashier, salesperson, drivers, or customer service representative (Figure 7).

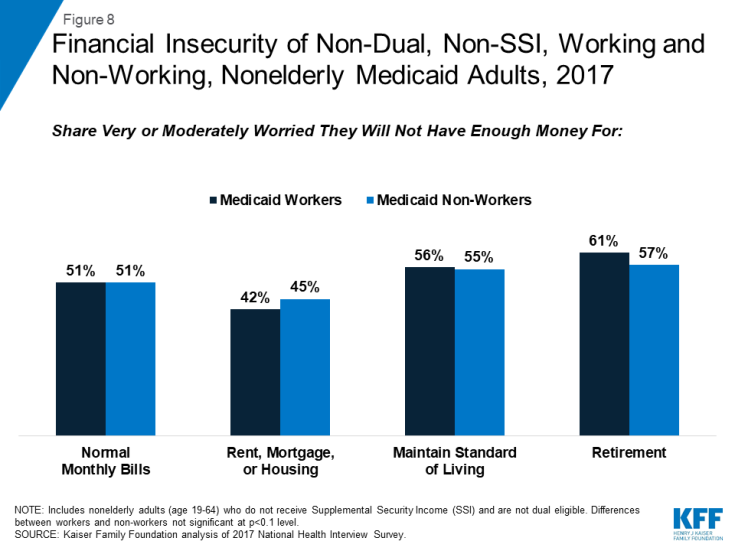

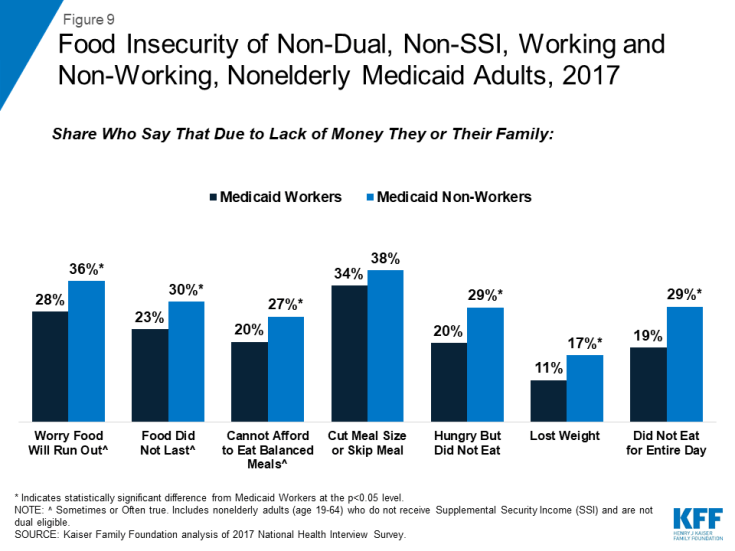

Even when working, adults with Medicaid face high rates of financial and food insecurity, as they are still living in or near poverty. Half report that they are very or moderately worried that they will not have enough money to pay normal monthly bills, and more than four in ten say they are very or moderately worried about having enough money for housing (Figure 8), rates similar to non-working adults with Medicaid. While income gained from work can improve financial security, this pattern shows that low-income workers still face substantial insecurity given the nature of their jobs. Additionally, people who meet Medicaid work requirements through participating in volunteer activities will not gain income to improve their financial security. More than a quarter (28%) of working and 36% of non-working Medicaid adults say they sometimes or often worry that food will run out, and high shares also report that they have experienced problems such as food not lasting before funds were available to buy more, having to cut meal size or skip meals, not eating due to lack of money, losing weight, or not eating for an entire day (Figure 9). While food assistance programs are available to low-income people, these programs do not reach everyone who faces food insecurity; among all Medicaid adults, only 29% live in a household that receives food assistance, and more than a quarter (26%) of working Medicaid adults live in a household that receive food assistance.

Figure 8: Financial Insecurity of Non-Dual, Non-SSI, Working and Non-Working, Nonelderly Medicaid Adults, 2017

Figure 9: Food Insecurity of Non-Dual, Non-SSI, Working and Non-Working, Nonelderly Medicaid Adults, 2017

What barriers to work and reporting requirements do Medicaid adults face?

Work requirement waivers generally require beneficiaries to verify their participation in certain activities, such as employment, job search, or job training programs, for a certain number of hours per week or verify an exemption to receive or retain Medicaid coverage. Exemptions to work activities may include medical frailty, attending school, care-giving responsibilities and others. This section highlights barriers that enrollees may face in working or reporting work or exemptions to work.

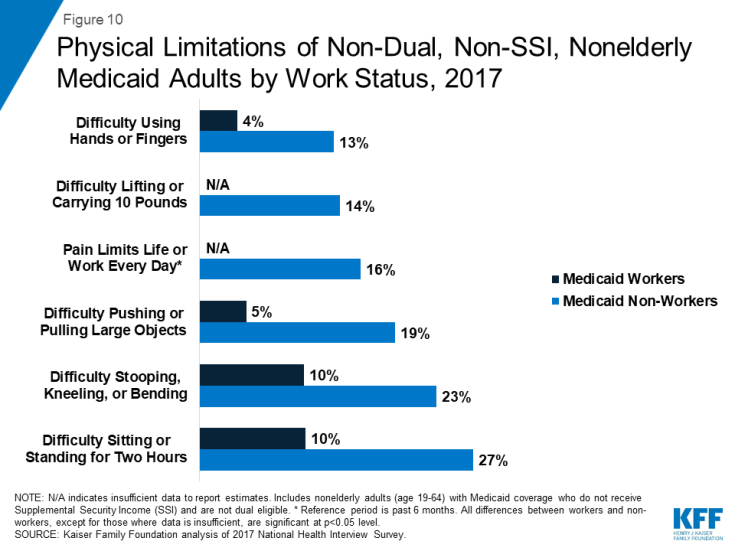

There are high rates of functional disability and serious medical conditions among Medicaid adults, especially among those not working. More than a third (34%) of those not working live with multiple chronic medical conditions such as hypertension, high cholesterol, arthritis, or heart disease, and half (51%) have any functional limitation, including mobility, physical, or emotional limitations. Many Medicaid adults who are not working report physical health problems that could limit their ability to work, such as daily, activity-limiting pain, difficulty standing or sitting for two hours, difficulty stooping, bending, or kneeling, using hands or fingers, or carrying 10 pounds, compared to Medicaid workers (Figure 10). Many have mobility restrictions that can be severe and may limit employment options: among those not working, nearly a fifth (18%) report difficulty walking 100 yards, 23% report difficulty walking up or down 12 steps, and 7% report the use of equipment or help to get around. Mental health conditions can also impede an individual’s ability to work. More than a third (35%) of non-working Medicaid adults report depression and more than one in ten (12%) report difficulty participating in social activities.

Figure 10: Physical Limitations of Non-Dual, Non-SSI, Nonelderly Medicaid Adults by Work Status, 2017

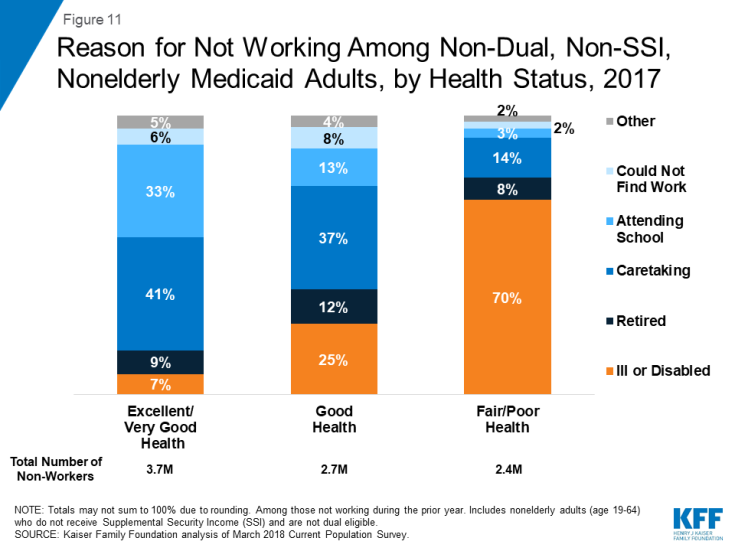

Going to school or care-taking responsibilities are other reported barriers to obtaining paying work. Even among those unlikely to meet medical frailty exemptions (the so-called “able bodied”), many could be exempt from complying with a work requirement policy for other reasons. Among those in excellent or very good health, nearly three fourths (74%) of those not working say it is because they are in school (33%) or are a caretaker (41%) (Figure 11).

Figure 11: Reason for Not Working Among Non-Dual, Non-SSI, Nonelderly Medicaid Adults, by Health Status, 2017

Many Medicaid adults do not use computers, the internet or email, which could be a barrier in finding a job and in complying with work reporting requirements. More than a quarter (26%) of Medicaid adults report that they never use a computer, 25% do not use the internet, and 40% do not use email (Figure 12), which may pose a barrier to both gaining a job and complying with reporting requirements under state waivers. For example, when it was in effect, Arkansas’ waiver required beneficiaries to set up an on-line account and use this account to report work activities and exemptions (reporting by phone was added as an option in December 2018).

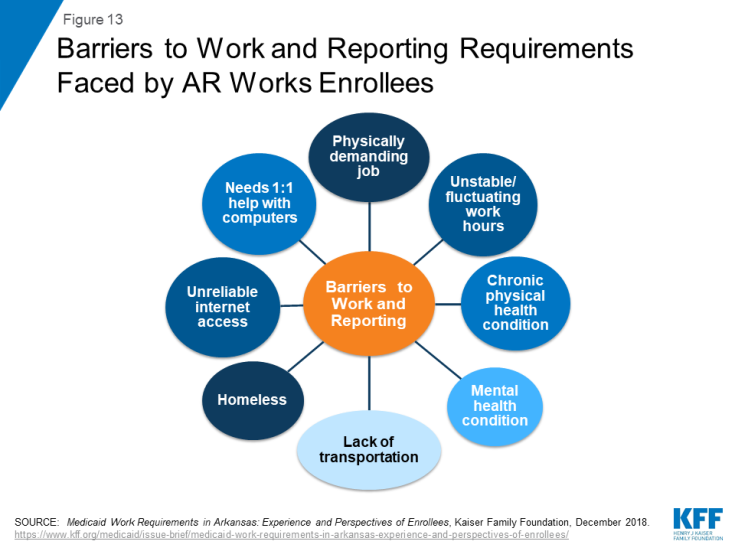

Research shows that enrollees report a range of barriers to complying with work and complex reporting requirements. Interviews with enrollees in Arkansas show that enrollees face many barriers in complying with both work and reporting requirements (Figure 13). Another report examining state data shows that measures to provide safeguards intended to protect coverage for people with disabilities and others who should not have been subject to the requirements are complex and hard to use. This experience is consistent with findings that TANF work requirements adversely affected people with disabilities who likely were eligible for an exemption based on a disability but did not obtain one.

What are the potential implications of Medicaid work and reporting requirements?

People who remain eligible for coverage could lose coverage as a result of work and reporting requirements. In Arkansas, over 18,000 people lost coverage when the work and reporting requirements were in place from August to December 2018. A small share of those who lost coverage reapplied and regained coverage when they were able to do so at the beginning of 2019. An earlier KFF analysis of potential nationwide reductions in Medicaid coverage if all states implemented work requirements estimated that most disenrollment would be among individuals who would remain eligible but lose coverage due to new administrative burdens or red tape, and only a minority would lose eligibility due to not meeting new work requirements. Updated analysis shows that estimated disenrollment ranges from 1.5 million to 4.1 million under a range of coverage loss assumptions considered (assumptions were based in past experience with reporting and work requirement policies). Establishing nationwide work requirements was included in the Administration’s proposed budget for FY 2020.

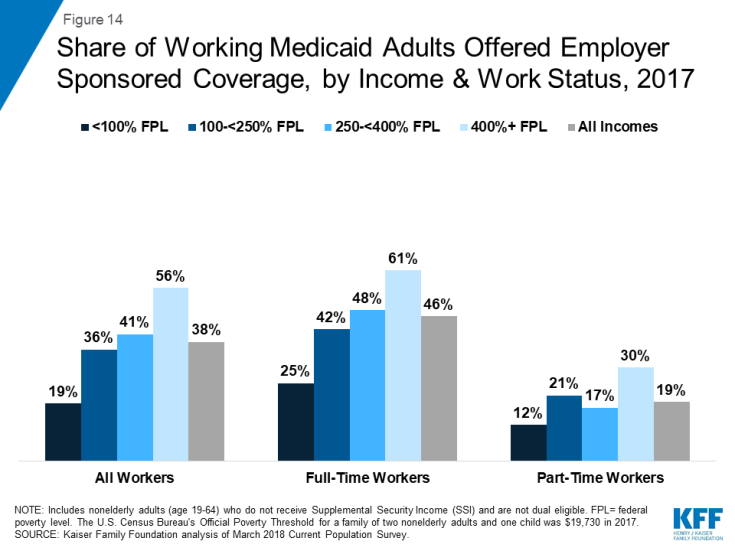

Work requirements may not result in increased employment or employer-based health coverage. Arkansas enrollees reported that new work requirements did not provide an additional incentive to work, beyond economic pressures to pay for food and other bills. Another study found that work requirements in Arkansas did result in significant changes in employment. Among individuals who may find work, low-income jobs are not likely to come with employer-sponsored insurance (ESI). ESI offer rates are low among poor (below 100% FPL) and low-income (between 100 and 250% FPL) workers who work full-time (25% and 42%, respectively). Very few part-time workers, especially those with low-incomes, receive an employer-sponsored offer of health benefits (Figure 14).

Figure 14: Share of Working Medicaid Adults Offered Employer Sponsored Coverage, by Income & Work Status, 2017

Loss of coverage could have negative implications for a person’s ability to work and can also increase uncompensated care for providers. Enrollees in Arkansas noted that Medicaid coverage enabled them to work by covering medications and services needed to manage mental health, asthma, gastrointestinal conditions, and other chronic health conditions. Without coverage, these conditions could worsen and interfere with enrollees’ ability to work or their ability to look for work and also could result in emergency room visits or preventable hospitalizations. In addition, providers anticipated that coverage losses tied to work requirements could result in increased uncompensated care for providers.

Looking Ahead

As litigation about Medicaid work and reporting requirements in several states moves ahead in the courts, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and some other states continue to pursue these waivers. An appeal currently is underway in the DC Circuit after a federal trial court stopped implementation of Arkansas’ work and reporting requirements in March 2019, and prohibited Kentucky’s waiver from going into effect in April as planned. On July 29, 2019, the court set aside the Granite Advantage Health Care Program demonstration, approved by CMS on Nov. 30, 2018. Implementation of the work requirement was stopped unless and until HHS issues a new approval that passes legal muster or prevails on appeal. Previously, on July 8, 2019, New Hampshire enacted legislation that allowed for the suspension of the work requirement’s implementation up to but not after July 1, 2021, and suspended the work requirement through Sept. 30, 2019. As of July 2019, Indiana is the only other state to have implemented a work requirement waiver; six more states have approved waivers that are not yet implemented. Arizona has submitted a request to CMS to delay implementation of its work requirement beyond the January 2020 date. Another seven states have waiver requests pending with CMS, including states that have not adopted the expansion. The outcome of the pending litigation, experience of states’ implementation of approved waivers and the outcome of pending waiver requests in non-expansion states will have implications for Medicaid enrollees and for states seeking to adopt similar policies.